The day e-scooters hit town

They appeared at dawn, under the incredulous gaze of France’s early risers and the foggier one of those only just heading home from their night out. Lined up like lead soldiers outside metro station entrances, they sat awaiting their innocent prey.

And just like that, the “evil e-scooter” arrived in town.

Since their sudden appearance, they have often been scorned and handed their final sentence. These droves of multi-coloured devices (which we French call trottinettes and not ‘scooters’, like in English, which to us are mopeds) have littered our pavements and are taking advantage of our streets for mercantile purposes. They have suffered the worst fates imaginable, too, such as destruction, system hacking and drowning, and are even banished from some lands – such as Nantes, for example.

Emotional reactions aside, if we scratch beneath the surface of the issue, we see that not only is the e-scooter a symbol of a much deeper urban mobility revolution, but that its sudden appearance could permanently alter the way we innovate in the urban space.

MICROMOBILITY ANATOMY

One distinctive feature of this new category of vehicles is how diverse it is in nature. Micromobility solutions can be mono-wheel or multi-wheel, come with or without a handlebar, possibly motorized, often shared, and the list goes on. All of a sudden, the old-fashioned bicycle finds itself surrounded by myriad new vehicles which are developing so fast that it is hard to keep up. One thing alone is certain – these are not the last new vehicle types that we will see riding our streets.

The fact is that micromobility, whether mono-wheel or two-wheel, is going to become more popular in cities. And one of the reasons is that it offers public transport users a solution for the first or last mile of their journey.

An attempt to outline a definition for micromobility gives us this: Vehicles that are lighter than their payload, zero emission, and, above all, unenclosed. And it is probably this latter feature that holds the most appeal for city use. By creating no screen between the city and the user, micromobility provides an amazingly effective transportation solution, which, at the same time, gives its user almost the same experience as a pedestrian – they can stop to chat with someone or to look in a shop window, for example. This also means that micromobility users are vulnerable, unprotected, and directly exposed to the rain, the city and other people.

While the famous free floating or dockless e-scooters have come to symbolize the sudden rise of micromobility in cities, in their shadow hides the successful uptake of personally owned devices, in particular electric-assist bikes. A whole new generation of users have begun using personal mobility devices for increasingly complex everyday travel – and we are talking here of much less experienced users than those tweeting the hashtag #bike2work to document their bike journeys via helmets fitted with GoPro® cameras.

AN OPPORTUNITY FOR CITIES?

Compared with micromobility, cars don’t size up. And size is in fact where the latter fall short. There where cars – even electric ones – are constrained by their ever-increasing bulkiness, bikes and scooters have an extraordinary power-to-weight ratio, making them more energy efficient. Other advantages are that they are zero emission and less dangerous for other city users, too. However, it is their small footprint that makes them particularly brilliant mobility solutions. Because the key unit of measurement for cities is not litres of fuel, mph or kilowatt, but square metres. And the reason is that cities are finite spaces and public spaces even more so.

Surface area occupied by different modes of transport both moving and stationary calculated on an individual passenger basis – a cyclist takes up 28 times less surface area than a car user and a pedestrian walking 70 times less. Data source: KiM Netherlands Institute for Transport Policy Analysis

Micromobility could also fill mobility gaps, particularly where it is combined with public transport. With a free floating or personal device that can be boarded onto a tram or metro, door-to-door journeys that would be too complex to achieve with public transport alone become possible, using micromobility for the first and last mile(s). Thus there is potential for two modes to resonate, with each focusing on what it does best – public transport for effective, high volume transportation on fixed routes, and micromobility as a solution for personal transportation needs anywhere within the urban fabric. All of a sudden, urban transport has a much greater geographical reach and can potentially become more efficient than one could ever have hoped.

This being so, could micromobility trigger the much-discussed modal shift from the car to more sustainable modes of transport that we have been seeking for decades?

MOVING ON FROM THE STATUS QUO

If we are to believe what we see in the press and on social media, the status quo is not about to budge for now. Everyone has sought to condemn the arrival of these hordes of scooters that have invaded Paris in the most crushing terms. Let’s face it, it has been a real culture shock.

On the one hand, you have the start-ups whose are centred exclusively on their users and the millions of kilometres that they cover in all of the world’s major cities. These are lean structures which focus on the short term and on surviving, and which see public space as a sort of infinite web with a few more constraints than usual. “Don’t ask for permission, ask for forgiveness” is their mantra. Barbarians some call them.

On the other hand, you have the city authorities who aren’t accustomed to anyone other than them taking initiatives in the public space, and who have the long term and all of the city’s residents in mind. This boom in new entrants is a mystery for public stakeholders. In some cities, the policy has been one of laissez faire, with a few rules improvised down the line to sort out the mess. In others, barriers are being created in the hope that the “bloodthirsty hordes” won’t land in the night...

If there is a topic that crystallizes tensions, it is indeed the parking of these free floating scooters. Because as well as genuinely cluttering up the streets, the scattering of these devices here, there and everywhere creates a sense of chaos and harms the readability of public space. And this is a very sensitive issue, as this chaos is affecting the sidewalks, which is the heartbeat of the city.

View of a cluttered Santa Monica sidewalks, California, January 2019

Over and above the (not so complicated) issue of regulating free floating services, though, these tensions are an absurd demonstration of how limited the current spatial organization is – sidewalks have become so narrow that there isn’t even room to park a few scooters. And free floating devices are not the only issue here because there is in fact no room to park or comfortably use personal e-mobility either. The elephant in the room that nobody wishes to see is, of course, the car. The time has come to challenge the status quo that gives priority to cars and to make room in cities for micromobility, which is a much more efficient way of moving people. But a modal shift will not happen without a spatial shift.

ACCELERATING CHANGE

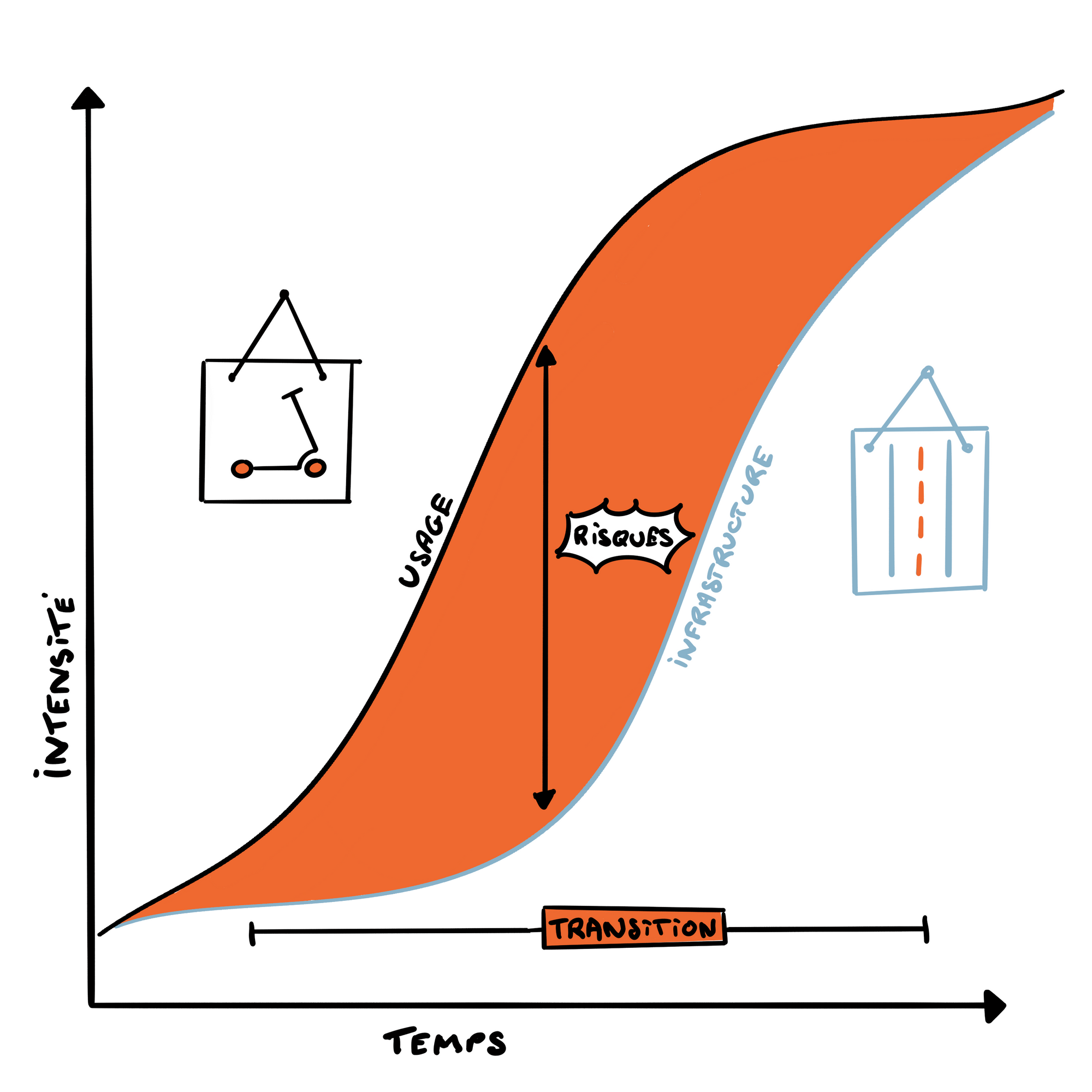

It is time to speed up the transition because cities are entering a risk zone. For a mobility mode to emerge smoothly, the appropriate culture and infrastructure must be developed in parallel. Though, while micromobility is clearly taking off, the necessary culture and infrastructure are considerably lagging behind. This places cities in a dangerous transition phase, reminiscent of the painful period that US cities underwent in the 1920s, with the sudden emergence of cars in urban areas which were not (yet) prepared for it.

The fact that e-scooters are being ridden on sidewalks is a good illustration of just how immature our culture is in this area – e-scooters should of course not be on sidewalks at all. In all probability, this problem will be resolved, just as we have managed to silence mobile phones in French train carriages. It is just that we still associate scooters with the playful realm of childhood and their rules of use are only just being made clear.

This happy families card game was distributed by the city authorities of Nantes in 2013. For the father riding a scooter, it says “My place is on the sidewalk!” However, since then, the Mobility Act has been passed and since September, e-scooters (and other “Motorized personal mobility devices”) are prohibited on sidewalk and must be ridden on cycle paths or, where there are none, on roads.

Adapting infrastructure to meet the boom in micromobility will be a much harder challenge. In France, the development of cycle networks is part of the long cycle that is the redevelopment of public space. Too often, an approximate approach has been taken to cycle path development, with lanes created on an ad hoc basis where they would fit, without questioning the place of cars. So, what’s the picture? Cycling conditions have generally improved for the experienced cyclist, but networks are fragmented, quite unsafe and unsuitable for the needs of new users. To limit the length of the transition phase, cities must start accelerating the renewal of infrastructure and adapt to emerging mobility modes. This also means making room for a greater number of users – users with less experience on faster devices – to travel around in sufficiently safe conditions. In other words, this means proper networks offering seamless and efficient mobility, rather than just narrow bike lanes designed not to be too much of a nuisance for cars.

RETHINKING SPATIAL ORGANISATION

Let us not be mistaken, adapting cities is not just a technical or budgetary matter, it requires a change of mind-set and a new set of goals for public space development:

- Moving people around, and not vehicles: The key performance indicator needs to be the number of people transported. In a spatially constrained public space, modes that use less space must logically be favoured.

- Eradicating the Swiss-knife syndrome: Anyone with experience in DIY knows that a tool that does everything, does nothing well. The same goes for streets. Permanently searching for a compromise between the different mobility modes systematically results in penalizing them all. Every street needs to give priority to an individual mode.

- Considering micromobility as a serious form of transportation: It, too, needs reliable infrastructure that is clean, free from carelessly parked vehicles (nicknamed #gcum or “garés comme une m..” in French), separated from other modes and safe.

Once these essentials are in place, instead of placing restrictions on these devices, we will need to start organizing space better. There isn’t room in cities to devote streets to every type of vehicle or device and infrastructure cannot evolve quick enough to keep up with the new developments in the field. Instead of regulating each individual vehicle type, let us organize space according to speed. There would be slow lanes (6 to 8 kmph) to ensure a peaceful environment for pedestrians, “low-stress” lanes (20 to 25 kmph) which would be suited to micromobility, urban thoroughfares (40 to 50 kmph) for motorized vehicles and, finally, public transport routes. The challenge, of course, is to ensure that all users abide by these speeds within the space they must share. Until we have technologies that automatically restrict speeds, streets must be designed to accompany the speed rules. Ridiculous examples of 30 kmph zones have shown us that merely sticking a sign up in town has no real impact.

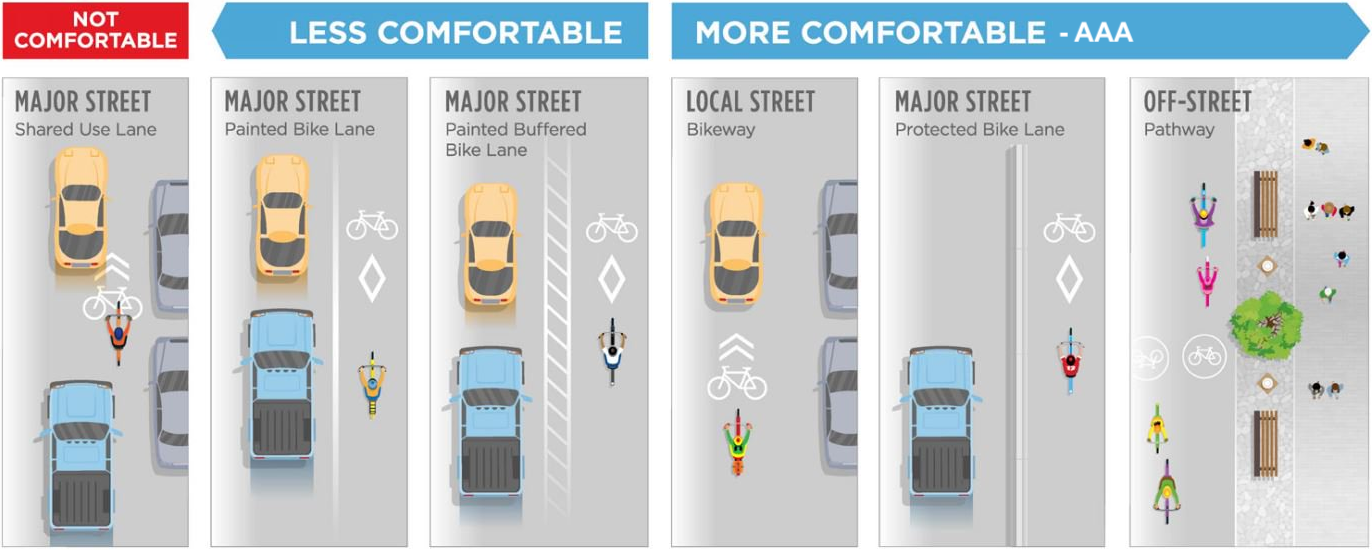

There is no one-solution-fits-all answer for introducing micromobility pathways or lanes, however much inspiration can be drawn from what others have tried. Take for example the AAA Guidelines of the City of Vancouver, Canada.

The City of Vancouver’s guidelines on how to organize the cohabitation of cars and cyclists, or how to go from the “urban jungle” to a city that is comfortable for all. © AAA Guidelines, City of Vancouver

These guidelines provide design recommendations for “low-stress” streets or pathways with the aim of making them accessible for all ages and abilities (AAA). They outline how to share space safely, or where a physical or visual separation is required to prevent interactions between different types of traffic, depending on the context. The proposed infrastructure is clearly an improvement and would make this transition phase smoother, however such designs require room...

INNOVATING IN CITIES

And it is easy to see that it is cars that need to give up a little room. Building networks of low-stress lanes so that micromobility users can ride comfortably around our city centres will therefore mean tackling the real issues related to acceptability – and when it comes to getting rid of parking spaces, discussions are bound to be heated. Resistance to change is logical and legitimate, but what we have here is more than a question of hostility to a known project; it is a fear of the unknown. Faced with uncertainty, everyone tends to imagine the worst. Tactical urbanism techniques can help to reduce this uncertainty – and the associated resistance – by allowing us to temporarily test urban transformations in real life, before making them permanent... or reverting them. This approach has proven to work if interventions are genuine and supported by a real comparative assessment, with a truly flexible project.

“Tactical urbanism” at work in the city of Providence in the US state of Rhode Island, with a clear separation and demarcation of lanes. © James Kennedy, Transport Providence

Behind the idea is the sandbox concept that is so important in software development, or in other words, an isolated environment in which tests can be performed without any risk of doing damage to the overall system. Several city councils in the US have implemented this type of sandbox for free floating systems, more often allocating time rather than space to experiment “pilot programs”. Rather than seeking to decide definitive regulations for emerging services, they have developed temporary rules by which operators must abide. These cities also demand access to operational data in order to constantly assess how the system performs. Based on concrete results from these trials, regulations are adapted and market access is gradually opened up, allowing more operators and more free floating devices onto the streets.

A new challenge has emerged for local authorities. This is the need to understand technology cycles, as well as how innovative services operate and what impacts they have on cities, so that we can effectively regulate innovations and ensure that their impact is positive. This means learning to respond on an everyday basis to the sudden appearance of new uses while at the same time keeping an eye firmly on the long term picture, so as not to succumb to the temptation of altering the city for the latest development on the scene.

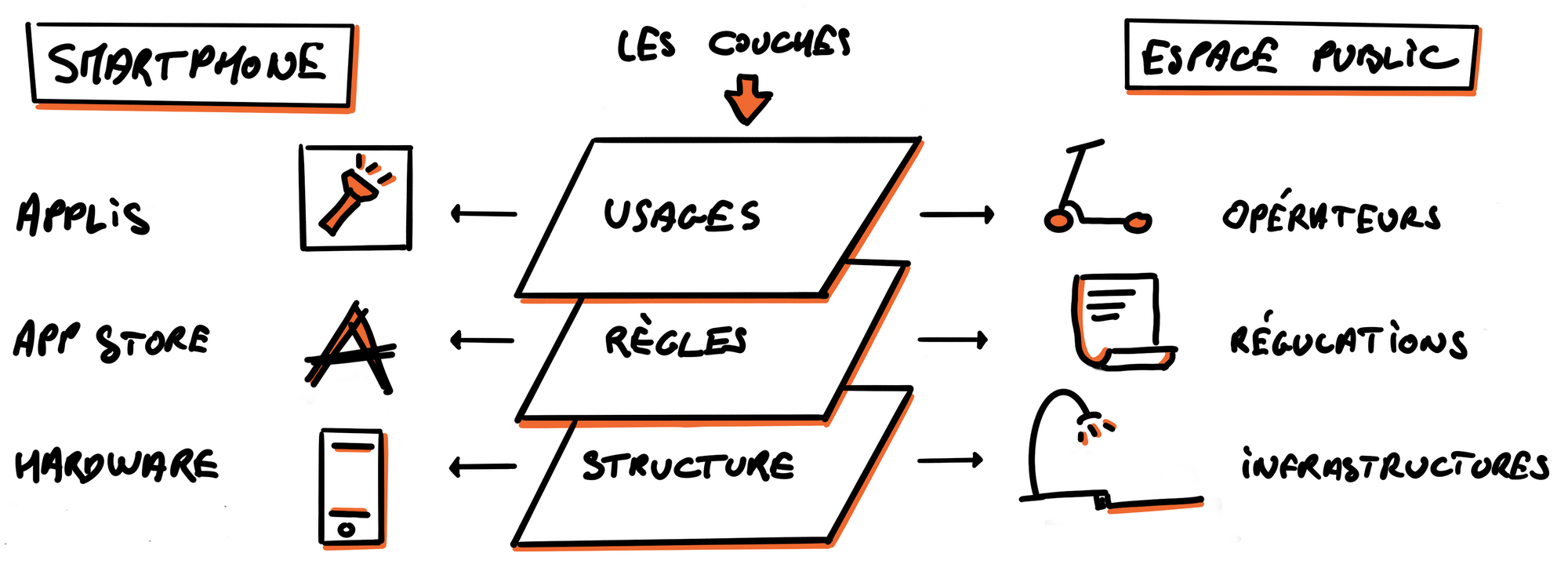

The smartphone, although somewhat a simplified analogy, offers a good illustration of how city and public space management needs to change, with a segmentation of overlapping layers. The lower layer represents the infrastructure (here the smartphone hardware), which evolves slowly to adapt to structural changes, such as the rise of micromobility for example. The very volatile upper layer represents the uses (e.g. the apps or free floating services), which emerge, evolve and disappear every day.

Today, we still too often lack this intermediary layer of regulation and thus structure the use of public space without taking account of new uses to come. This is something that is well managed by smartphone app stores, which control the functioning of applications (access to functionalities, data, prices, and so on), without, however, stifling innovation among developers.

The general rise in micromobility, and not just the noticeable influx of free floating scooters, is thus an opportunity to rethink how we physically organize public space as well how cities approach innovation. For city authorities, understanding the third party’s culture, developing the practice of experimentation and implementing a dynamic approach to public space management are changes that are all as important as creating the appropriate infrastructure for micromobility. These changes will be crucial if we want to harness the full potential of the next innovation, whose name we can yet only guess: autonomous vehicle, delivery robot, jet pack... or free floating pogo stick?

Sylvain Grisot · Septembre 2019