The Street, by Google

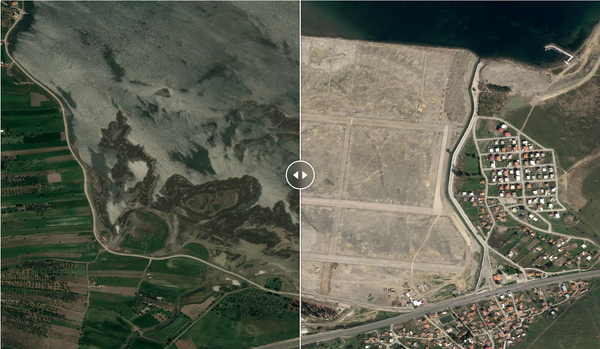

For those who might have been living on a base on Mars for the last ten years, let me tell you that Google is not just a web company. Today, Google is part of Alphabet Inc., which is also the parent company of a whole range of businesses with a much wider scope than internet services, such as home automation, biotechnology, autonomous vehicles, drones, AI and even – you’ve guessed it – street design! That’s right. With its subsidiary Sidewalk Labs, Google (now Alphabet) proudly claims to be “reimagining cities from the internet up”, and is planning to “prototype” its urban solutions on a 300-hectare (741-acre) area of wasteland in Toronto, in a project known as Quayside.

This is where this article’s anti-GAFA rant would usually start, with the kind of criticism that is mostly valid, but never completely accurate and always a little over-simplistic. But that is not what this article about – others have tackled that topic better than I could.

When a company like Google invests such resources and hires such a talented team to embark on an urban laboratory project, it is worth taking a closer look. The company makes it very clear that this is not an umpteenth #smartcity project shoving “3.0” technologies into the urban environment.

This is indeed a true effort by high-calibre urban planners, architects and engineers to rethink how cities are built, while enjoying access to cutting-edge technologies. It is also a major shift in terms of perspective and methodology, where a model inspired directly by the digital business culture is – at last – being applied to city design. The project also bears the classic features of these former start-ups that have grown (too) big, like transparency on the key elements of work – which comes from an open-source culture – and a great opacity on contractual and financial matters.

So why reinvent the street?

To try and answer this, let’s now look in detail at one of the latest publications from the Sidewalk Labs team: the Street Design Principles, appropriately in their 1.0 version. The aim of this document is both straightforward and vast: to provide guidelines for designing public spaces that make the best possible use of technological advances, to make streets more comfortable, safer and efficient in getting people where they need to go. It’s an impressive plan. We are looking here, of course, at a document with a general scope, which is no doubt the result of thinking carried out specifically for the Quayside project, but which is intended to have a greater resonance.

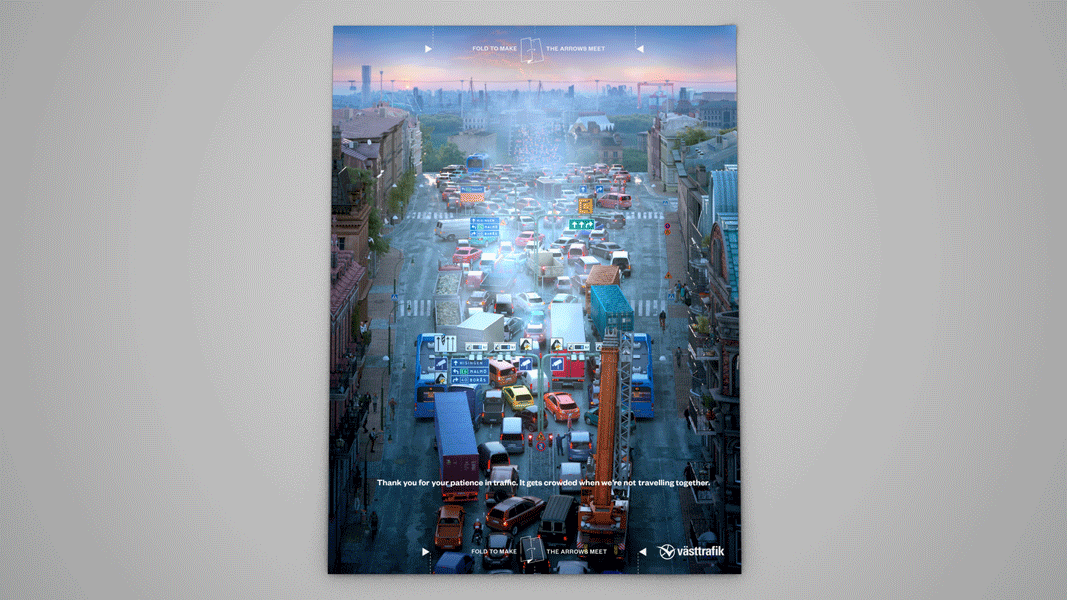

The initial starting point is a fact with which we cannot argue: something is wrong with our street design approach. Cars have clearly won the battle to dominate the streets that began several decades ago, yet today they sit in endless traffic congestion with their AC on full blast. In today’s urban organization, we want city streets to simultaneously offer a fluid throughput of vehicles, safety for non-motorized transport users and comfortable conditions for pedestrians, all within a restricted space. Bizarrely though, it doesn’t work at all. The flow is too slow for cars and too fast for the other groups of users. It is a case of the Swiss army knife syndrome, where one thing is designed to do everything, but in fact does nothing well.

Technology is the solution, but what is the problem?

The teams at Sidewalk Labs have not succumbed to the “solutionism” that often shapes urban innovations. I’m talking here about those innovation competitions whose participants focus on searching for an actual problem to solve with their technology, rather than developing a useful technology to solve a real problem.

Here the strategy is clearly to leverage technologies to improve the performance of street space (which is limited), through a variation of uses, speeds and costs.

The specific goal behind this is a sound one: to move people (no matter what their mode of transport) – and not cars – around better. And that is a paradigm change.

So what are these technologies which are going to make our streets better? The most obvious building block involves a profusion of sensors stuffed in people’s pockets and in every corner of the city, in order to provide a full-scale digital picture of things. This stream of data, when combined with machine learning, will be used to optimize the city in real time or even in predictive mode. But apart from traffic signalling, what systems can have a real-time effect?

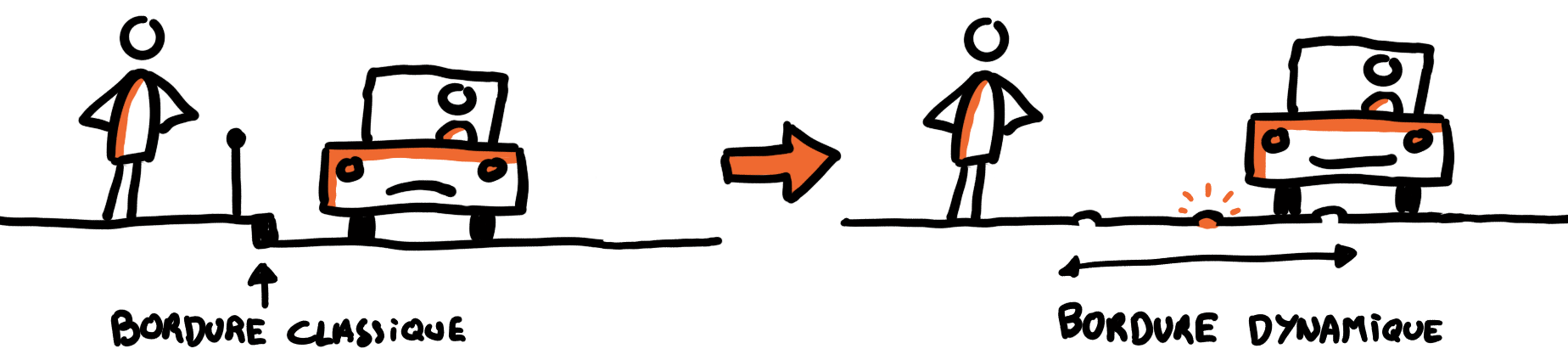

This is where the rather fascinating concept of the “dynamic curb” comes in. The idea is to be able to constantly adapt the allocation of street space as needed, by removing the traditional curb, which represents an inflexible separation between the street and the pavement, in the form of an 18 cm step. Raised pavements are therefore eliminated and the allocation of space is signalled by LEDs embedded in the ground, which light up differently according to needs – the vehicle lane required in the morning becomes a pedestrian-only space at lunchtime, where a drop-off zone for a passing Uber can even be made to appear for a moment…

Curbs, height differences and bollards are thus replaced by LED-embedded hexagonal concrete paving inspired by a French innovation. Very well, but how do you enforce a simple light signal when it is already difficult making drivers comprehend that a cycle path is not a drop-off zone, and when SUVs are taking up more and more curb space?

Sidewalk Labs

The whole intellectual edifice relies on a new development: the CAV, or “Connected and Autonomous Vehicle”. Rather than base its entire design on driverless vehicles that may be some time coming, the teams at Sidewalk Labs are banking on an altogether enticing substitute: the car made civilized by technology.

The CAVs featured in the design respect 30 kph zones, keep in lane, don’t park on sidewalk with their hazard lights on, and slow down courteously when they near a pedestrian or cyclist. We imagine that CAVs are also zero-emission, even though this is not specified. In short, these are cars WITH a driver, but whose options are restricted. So is this future near? The technological leap is not that huge (basic e-scooters are already capable of slowing down automatically in pedestrian areas), however the cultural gap is abyssal.

Design principles for four standard street types

So, CAVs enable the implementation of dynamic curbs and special signage, powered by sensor data processed using artificial intelligence. It all hangs together, and why wouldn’t it? Based on this, the Sidewalk Labs team proposes to redesign street space based on four simple principles, which can be viewed in two pairs:

- Exit the Swiss knife syndrome – here a priority mode of transportation is selected for each street type and street design is tailored to that mode (Principle 1). The speed of a street is dictated accordingly by its priority mode (Principle 2).

- Street space is separated dynamically according to the different uses, using techniques such as the “dynamic curb” and signage (Principle 3), and wherever possible space is recaptured for uses other than vehicles (Principle 4).

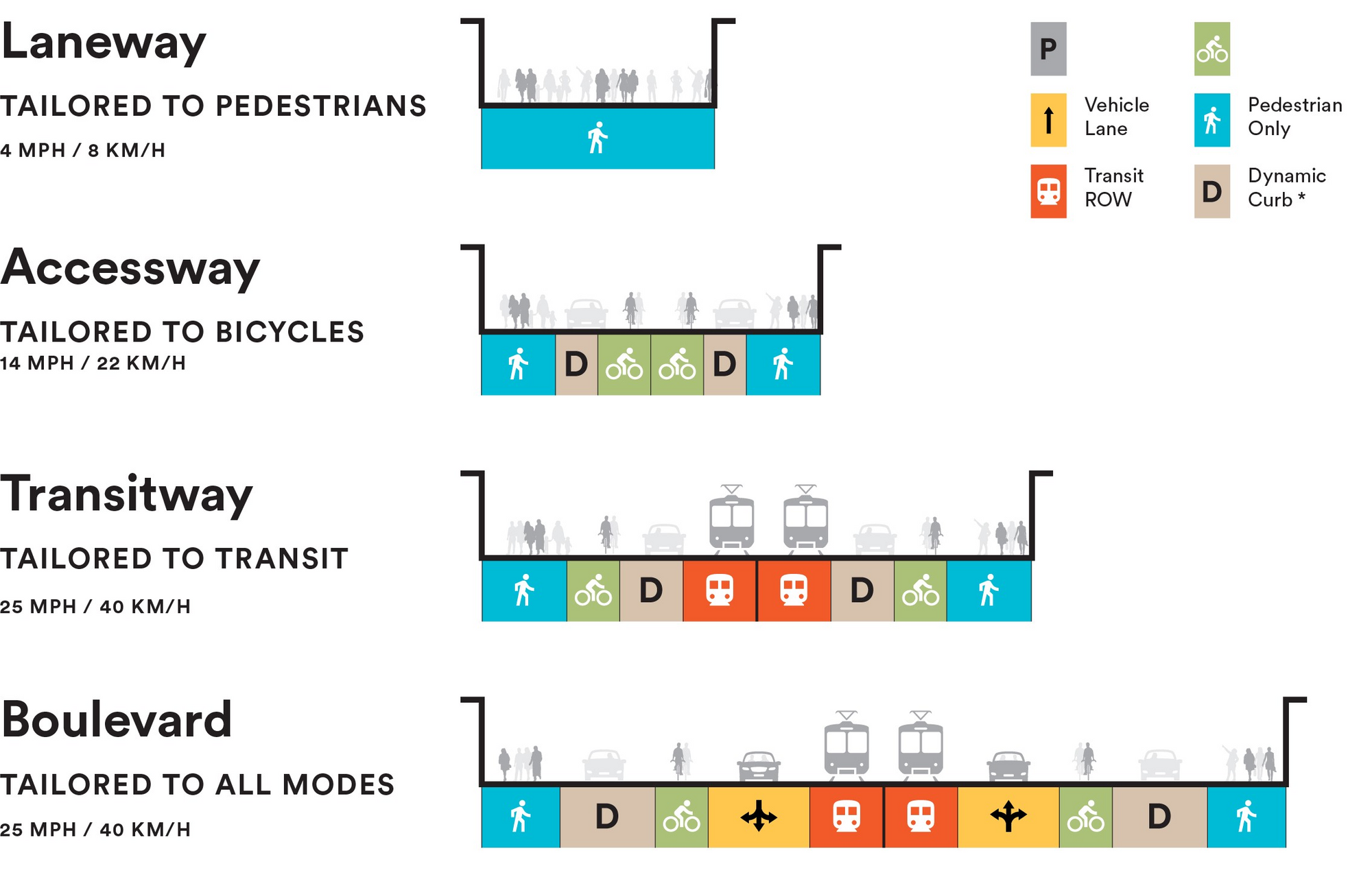

On the basis of these principles, four very different street types are suggested. Each has a priority mode of transportation and a maximum speed, with a portion of space allocated dynamically. Most of this space is recaptured from what was previously parking, which is systematically removed in all the street types. Looking in detail, this results in:

- Laneways. These are 11-metre-wide streets devoted primarily to pedestrians, but which can also accommodate CAVs or micromobility modes (bicycles, scooters, etc.) up to a speed limit of 8 kph.

- Accessways. These form a seamless network enabling the efficient transit of micromobility modes through dedicated lanes and an optimized speed. CAVs may also be allowed to used them, within a speed limit of 22 kph.

- Transitways. These streets enable an efficient throughput of public transportation and CAVs, and allow a maximum speed of 40 kph.

- Boulevards. These accommodate all transit modes. They are the only streets that traditional cars (like yours and mine) are permitted to use and off-street parking is accessible from them.

A cross-sectional view looks like this:

Sidewalk Labs

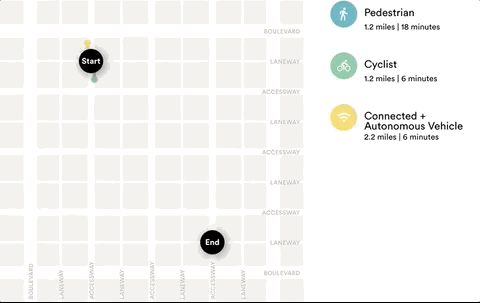

The speed limitations and better usability encourage users to opt for the street type that prioritizes their mode, even if to shorten the duration of their trip they have to take a longer route.

Sidewalk Labs

The conceptual work in the document is truly inspiring, especially for its focus on moving people rather than vehicles. It effectively introduces a design approach that considers the space required by different mobility modes, in the particularly confined environment that is urban public space.

Vasttrafik

However, the transition from concept to reality is no doubt more complex than it might seem.

These proposals bear the characteristics of both the orthogonal and hierarchically structured US city and the recently developed “Superblocks” in Barcelona which benefit from the very clear grid system of the Plan Cerdà. Such concepts are harder to directly apply to the organic urban fabric of European cities. Each of the proposed street types will probably need to be adapted to cater better for the intricacies of its specific urban environment, or perhaps even hybrid forms will be needed.

What we can take away though is this idea of prioritizing streets for one specific mode of mobility and tailoring both the design and speed to this mode. Rather than a recipe to apply, this is perhaps the first draft of a conceptual framework that can be used to establish dialogue locally.

What is rather intriguing is the place that these design principles give to CAVs. The idea of making cars civilized through technology is an interesting one and is no doubt an achievable challenge – slightly more accurate satellite navigation systems and the full digitization of public space are all that is lacking. The most difficult aspect will perhaps be convincing vehicle manufacturers and drivers to adopt such options, but it is certainly worth the effort.

What is most surprising though is the idea of allowing CAVs access to even the most pedestrian of the street design types. Why allow one or two tonne vehicles transporting just one person to access to the city centre? Even operating with a zero-emission propulsion system, the energy efficiency of such vehicles is terrible and the space they require a complete waste. The recent surge in micromobility options, in particular electric micromobility (especially e-bikes), new vehicle types (e.g. e-scooters etc.) and shared services (whether free-floating or not), offers new alternatives to the car for a wide range of users, which it would be good to see fully incorporated into public space design.

It is strange for that matter that the Sidewalk Labs team has not focused more on the potential offered by city micromobility, which goes well beyond the free-floating e-scooters that recently made the headlines. Travelling at speeds of up to 20 to 25 kph, micromobility offers a very effective alternative to the car. On the other hand, cycling in all seasons is clearly promoted with interesting technological ideas like the green light waves, below, that give cyclists green lights all along their journey:

SWARCO

These kind of Street Design Principles seeking to develop a systematic theoretical approach that can be applied in the real world, are always difficult to implement in the urban environment. Unlike software that we can decide to redevelop from scratch when no further development is possible, cities are real and impose a certain materialization of public space on us, as well a their uses, rules, user organization and economics.

So how do we approach the transition stage when the changes needed are so radical, for example altering the place accorded to cars? That is the great difference between designing an ideal city in the middle of a desert and rethinking a physically existing and inhabited urban environment. We will need theoretical documentation and technological solutions to engage a dialogue in the field, city by city, street by street...

So while this first version has some interesting ideas, it provides us with food for thought rather than a finished product. But it is only a first draft, and Sidewalk Labs invites you – sincerely I think – to take part in developing the second version: streetdesign@sidewalklabs.com.

Sylvain Grisot · Juin 2019